Scotland's Democratic Heritage

With the new Scottish parliament set to open for business, Magnus Linklater looks at Scotland's democratic heritage.

With the new Scottish parliament set to open for business, Magnus Linklater looks at Scotland's democratic heritage.

On July 1, 1999, the first Scottish Parliament to have sat for 292 years will open for business.

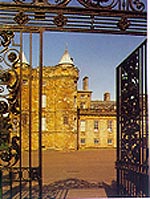

The 19th century Assembly Hall on the Royal Mile in Edinburgh, where the Church of Scotland holds its annual meetings, has been specially modernised for this historic occasion, with microphones, smart new seating, and a horse-shoe shaped debating chamber. But this is a temporary home, a staging-post on the way to the permanent building that will be ready in two years' time at Holyrood, down the hill, a stone's throw from the Palace of Holyroodhouse.

At the Assembly Hall, the 129 newly-elected members of parliament gathered for the first time. It was a milestone in the constitutional history of the United Kingdom. How did it all come about? How did Scotland gain its parliament in the first place, and how did it come to lose it?

Scotland's nationhood goes back more than a thousand years, to the ancient kings who first united Picts and Scots and began defending their land along a border defined and fortified under the Romans. The first parliament to be recorded was in 1293, but the institution certainly goes back far further than this. Robert the Bruce's victory at Bannockburn in 1314 established Scotland's de facto rights as a kingdom, and in 1320, the nobles, clergy and commons of Scotland, meeting at Arbroath, sent a declaration to Pope John XXII proclaiming their devotion to nationhood and liberty, "which no true man relinquishes but with his life." Today it is held in the Scottish Record Office in Edinburgh.

The whole thrust of the Declaration, and the origins of Scotland's democratic traditions, lies in the belief that the powers of the King are limited, and that if he acts against the interests of the kingdom, he may be deposed. In 1326, a parliament held at Cambuskenneth was attended for the first time by the so-called "thrie estates" - barons, clergy and representatives of the burghs.

It was this parliament of the three estates that, nearly 300 years later, passed the first Act of Union joining the two kingdoms of England and Scotland together and creating Great Britain. But Scotland still remained a separate nation, with its own representatives sitting in Edinburgh. The first king to sit on both thrones in 1603 was James Sixth of Scotland and First of England, the son of Mary, Queen of Scots. But though he united two countries, he alienated the Presbyterian clergy in Scotland by favouring the hierarchy of the bishops instead of the democracy of the kirk. He was attacked by Andrew Melville, the successor of John Knox, who called him "God's sillie vassal." The divisions thus opened up were to lead to the internal religious wars of the 17th century.

In 1632, under Charles I, the parliament moved into splendid new premises in Parliament Hall on the Royal Mile, next to St Giles' Cathedral, where, five years later, an Edinburgh woman, Jenny Geddes, made a famous protest over the introduction of the new Church of England prayer book by hurling her stool at the pulpit. It was the vacillation of the Stuarts, principally over religious matters, that finally led to their demise, when James VII of Scotland surrendered the throne to William of Orange, and went into exile, hurling the royal seal into the Thames as he fled. Weak as they often were, it should be remembered that their tenure over many centuries in Scotland qualifies them as the longest-reigning dynasty in European history.

It was under William and Mary, who inherited both thrones, that the process began which was to lead to the end of Scotland's parliament. When Mary's sister, Anne, came to power, pressure grew for a single parliament to represent all of Great Britain. No one should assume that the Union was achieved without opposition. Although there were those who argued that Scotland's trading position and the welfare of its economy would be greatly improved by a Union with England, the Act which brought it into being was bitterly fought.

The Duke of Hamilton at first opposed and then supported it. The Hamilton castle of Brodick on the Isle of Arran can still be seen, though the present Duke lives at Lennoxlove in East Lothian. The Duke of Queensberry, with his stronghold at Drumlanrig Castle, near Thronhill in Dumfriesshire, was a key supporter, as was Sir John Dalrymple, the Master of Stair, whose family has strong links to the New Hailes, near Musselburgh and Glenluce in Wigtownshire. Andrew Fletcher of Saltoun in East Lothian known as "the patriot" was the most vigorous opponent of the bill, and James Ogilvie, Earl of Seafield and the Lord Chancellor of the day, uttered the most famous phrase of them all when he said that the collapse of the Scots Parliament was "the end of ane auld sang." Duff House in Banffshire, where the Ogilvies came from, has been refurbished and is now an outpost of the National Galleries of Scotland.